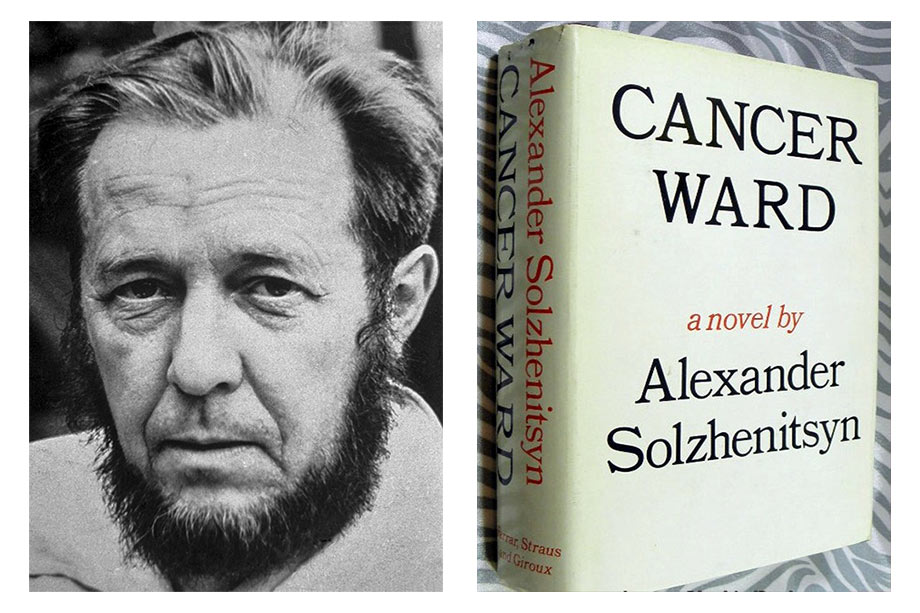

"Cancer Ward" is a semi-autobiographical novel by Nobel Prize winner in literature Alexander Solzhenitsyn.

Written in 1963-1966 based on memories of the writer’s treatment in the oncology department of a hospital in Tashkent in 1954.

In 1968, several European publishers published it in Russian, and in April 1968, excerpts in English appeared in the Times Literary Supplement in Britain without Solzhenitsyn's permission. An unauthorized translation into English was published that same year, first by The Bodley Head in the UK, then by Dial Press in the US.

In the USSR, the novel was banned for a long time and was first published only in 1990 in the magazine “New World”.

One of the chapters of the book, “Cancer of the Birch Tree,” is devoted to a discussion among clinic patients about the miraculous birch mushroom that cures cancer.

... ...

11. Cancer of the Birch Tree

In spite of everything, Saturday evening came as a sort of invisible relief to everyone in the cancer wing, no one quite knew why. Obviously the patients were not released for the weekend from their illness, let alone from thinking about it; but they were freed from talking to the doctors and from most of their treatment, and it was probably this which gladdened some eternally childish part of the human make-up.

After his conversation with Asya, Dyomka managed to climb the stairs, although the nagging pain in his leg was growing stronger, forcing him to tread more carefully. He entered the ward to find it more than usually lively. All those who belonged to the ward were there, Sibgatov too, and there were also some guests from the first floor—new arrivals as well as a few he knew like the old Korean, Ni, who had just been allowed out of the ward. (So long as the radium needles were in his tongue they had kept him under lock and key, like a valuable in a bank vault.) One of the new people was a Russian, quite a presentable man with fair, swept-back hair who had something wrong with his throat. He could only speak in a whisper. As it happened, he was sitting on Dyomka’s bed, taking up half of it. Everyone was listening, even Mursalimov and Egenberdiev, who didn’t understand Russian.

Kostoglotov was making a speech. He was sitting not on his bed but higher up, on his window sill, emphasizing thereby the importance of the moment. (If any of the strict nurses had been on duty he wouldn’t have been allowed to sit there, but Turgin was in charge, a male nurse whom the patients treated as one of themselves. He rightly judged that such behavior would hardly turn medical science upside down.) Resting one stockinged foot on the bed, Kostoglotov put the other leg, bent at the knee, across the knee of the first leg like a guitar. Swaying slightly, he was discoursing loudly and excitedly for the whole ward to hear:

“There was this philosopher Descartes. He said, ‘Suspect everything.’”

“But that’s nothing to do with our way of life,” Rusanov reminded him, raising a finger in admonition.

“No, of course it isn’t,” said Kostoglotov, utterly amazed by the objection. “All I mean is that we shouldn’t behave like rabbits and put our complete trust in doctors. For instance, I’m reading this book.” He picked up a large, open book from the window sill. “Abrikosov and Stryukov, Pathological Anatomy, medical school textbook. It says here that the link between the development of tumors and the central nervous system has so far been very little studied. And this link is an amazing thing! It’s written here in so many words.” He found the place. “‘It happens rarely, but there are cases of self-induced healing.’ You see how it’s worded? Not recovery through treatment, but actual healing. See?”

There was a stir throughout the ward. It was as though “self-induced healing” had fluttered out of the great open book like a rainbow-colored butterfly for everyone to see, and they all held up their foreheads and cheeks for its healing touch as it flew past.

“Self-induced,” said Kostoglotov, laying aside his book. He waved his hands, fingers splayed, keeping his leg in the same guitar-like pose. “That means that suddenly for some unexplained reason the tumor starts off in the opposite direction! It gets smaller, resolves and finally disappears! See?”

They were all silent, gaping at the fairy tale. That a tumor, one’s own tumor, the destructive tumor which had mangled one’s whole life, should suddenly drain away, dry up and die by itself?

They were all silent, still holding their faces up to the butterfly. It was only the gloomy Podduyev who made his bed creak and, with a hopeless and obstinate expression on his face, croaked out, “I suppose for that you need to have … a clear conscience.”

It was not clear to everyone whether his words were linked to their conversation or were some thought of his own.

But Pavel Nikolayevich, who on this occasion was listening to his neighbor Bone-chewer with attention, even with a measure of sympathy, turned with a nervous jerk to Podduyev and read him a lecture.

“What idealistic nonsense! What’s conscience got to do with it? You ought to be ashamed of yourself, Comrade Podduyev!”

But Kostoglotov followed it up straightaway.

“You’ve hit the nail on the head, Yefrem. Well done! Anything can happen, we don’t know a damn thing. For example, after the war I read something very interesting in a magazine, I think it was Zvezda.[1] It seems that man has some kind of blood-and-brain barrier at the base of his skull. So long as the substance or microbes that kill a man can’t get through that barrier into the brain, he goes on living. So what does that depend on?”

The young geologist had not put down his books since he had come into the ward. He was sitting with one on his bed, by the other window, near Kostoglotov, occasionally raising his head to listen to the argument. He did so now. All the guests from the other wards were listening too, as well as those who belonged there. Near the stove Federau, his neck still unmarked and white but already doomed, lay curled up on his side, listening from his pillow.

“… Well, it depends, apparently, on the relationship between the potassium and sodium salts in the barrier. If there’s a surplus of one of these salts, I don’t remember which one, let’s say sodium, then nothing harmful can get through the barrier and the man won’t die. But if, on the other hand, there’s a surplus of potassium salts, then the barrier won’t do its work and he dies. What does the proportion of potassium to sodium depend on? That’s the most interesting point. Their relationship depends on a man’s attitude of mind! Understand? It means that if a man’s cheerful, if he is stanch, then there’s a surplus of sodium in the barrier and no illness whatever can make him die! But the moment he loses heart, there’s too much potassium, and you might as well order the coffin.”

The geologist had listened to him with a calm expression, weighing him up. He was like a bright, experienced student who can guess more or less what the teacher is going to write next on the blackboard.

“The physiology of optimism,” he said approvingly. “A good idea. Very good.”

Then, as if anxious not to lose time, he dived back into his book.

Pavel Nikolayevich didn’t raise any objection now. Bone-chewer was arguing quite scientifically.

“So I wouldn’t be surprised,” Kostoglotov continued, “if in a hundred years’ time they discover that our organism excretes some kind of cesium salt when our conscience is clear, but not when it’s burdened, and that it depends on this cesium salt whether the cells grow into a tumor or whether the tumor resolves.”

Yefrem sighed hoarsely. “I’ve mucked so many women about, left them with children hanging round their necks. They cried … mine’ll never resolve.”

“What’s that got to do with it?” Pavel Nikolayevich suddenly lost his temper. “The whole idea’s sheer religious rubbish! You’ve read too much slush, Comrade Podduyev, you’ve disarmed yourself ideologically. You keep harping on about that stupid moral perfection!”

“What’s so terrible about moral perfection?” said Kostoglotov aggressively. “Why should moral perfection give you such a pain in the belly? It can’t harm anyone—except someone who’s a moral monstrosity!”

“You … watch what you’re saying!”

Pavel Nikolayevich flashed his spectacles with their glinting frames; he held his head straight and rigid, as if the tumor wasn’t pushing it under the right of the jaw. “There are questions on which a definite opinion has been established, and they are no longer open to discussion.”

“Why can’t I discuss them?” Kostoglotov glared at Rusanov with his large dark eyes.

“Come on, that’s enough,” shouted the other patients, trying to make peace.

“All right, comrade,” whispered the man without a voice from Dyomka’s bed. “You were telling us about birch fungus…”

But neither Rusanov nor Kostoglotov was ready to give way. They knew nothing about one another, but they looked at each other with bitterness.

“If you wish to state your opinion, at least employ a little elementary knowledge.” Pavel Nikolayevich pulled his opponent up, articulating each word syllable by syllable. “The moral perfection of Leo Tolstoy and company was described once and for all by Lenin, and by Comrade Stalin, and by Gorky.”

“Excuse me,” answered Kostoglotov, restraining himself with difficulty. He stretched one arm out toward Rusanov. “No one on this earth ever says anything ‘once and for all.’ If they did, life would come to a stop and succeeding generations would have nothing to say.”

Pavel Nikolayevich was taken aback. The tops of his delicate white ears turned quite red, and round red patches appeared on his cheeks.

(He shouldn’t be expostulating, entering into a Saturday afternoon argument with this man. He ought to be checking up on who he was, where he came from, where his background was, and whether his blatantly false views weren’t a danger in the post he occupied.)

“I am not claiming,” Kostoglotov hastened to unburden himself, “that I know a lot about social science. I haven’t had much occasion to study it. But with my limited intelligence I understand that Lenin only attacked Leo Tolstoy for seeking moral perfection when it led society away from the struggle with arbitrary rule and from the approaching revolution. Fine! But why try to stop a man’s mouth”—he pointed with both his large hands to Podduyev—“just when he has started to think about the meaning of life, when he himself is on the borderline between life and death? Why should it irritate you so much if he helps himself by reading Tolstoy? What harm does it do? Or perhaps you think Tolstoy should have been burned at the stake? Perhaps the Government Synod[2] didn’t finish its work?”

(Kostoglotov, not having studied social science, had mixed up “holy” and “government.”)

Both Pavel Nikolayevich’s ears had now ripened to a full, rich, juicy red. This was a direct attack on a government institution (true, he had not quite heard which institution). The fact that it was made in front of a random audience not hand-picked made the situation more serious still. What he had to do now was stop the argument tactfully and check up on Kostoglotov at the first opportunity. So he did not make an issue of it. Instead he said in Podduyev’s direction, “Let him read Ostrovsky.[3] That’ll do him more good.”

But Kostoglotov did not appreciate Pavel Nikolayevich’s tact. Without listening or taking in anything the other said, he continued recklessly putting forward his own ideas to an unqualified audience.

“Why stop a man from thinking? After all, what does our philosophy of life boil down to? ‘Oh, life is so good!… Life, I love you. Life is for happiness!’ What profound sentiments. Any animal can say as much without our help, any hen, cat, or dog.”

“Please! I beg you!” Pavel Nikolayevich was warning him now, not out of civil duty, not as one of the great actors on the stage of history, but as its meanest extra. “We mustn’t talk about death! We mustn’t even remind anyone of it!”

“It’s no use begging!” Kostoglotov waved him aside with a spade-like hand. “If we can’t talk about death here, where on earth can we? Oh, I suppose we live forever?”

“So what? What of it?” pleaded Pavel Nikolayevich. “What are you suggesting? You want us to talk and think about death the whole time? So that the potassium salts get the upper hand?”

“Not all the time,” Kostoglotov said rather more quietly, seeing he was beginning to contradict himself. “Not all the time, only sometimes. It’s useful. Because what do we keep telling a man all his life? ‘You’re a member of the collective! You’re a member of the collective!’ That’s right. But only while he’s alive. When the time comes for him to die, we release him from the collective. He may be a member, but he has to die alone. It’s only he who is saddled with the tumor, not the whole collective. Now you, yes, you!”—he poked his finger rudely at Rusanov—“come on, tell us, what are you most afraid of in the world now? Of dying! What are you most afraid of talking about? Of death! And what do we call that? Hypocrisy!”

“Within limits that’s true.” The nice geologist spoke quietly, but everyone heard him. “We’re so afraid of death, we drive away all thought of those who have died. We don’t even look after their graves.”

“Well, that’s right,” Rusanov agreed. “Monuments to heroes should be properly maintained, they even say so in the newspapers.”

“Not only heroes, everyone,” said the geologist gently in a voice which, it seemed, he was incapable of raising. It wasn’t only his voice that was thin, he was too. His shoulders gave no hint of physical strength. “Many of our cemeteries are shamefully neglected. I saw some in the Altai Mountains and over toward Novosibirsk. There are no fences, the cattle wander into them, and pigs dig them up. Is that part of our national character? No, we always used to respect graves…”

“To revere graves,” added Kostoglotov.

Pavel Nikolayevich had stopped listening. He had lost interest in the argument. Forgetting himself, he had made an incautious movement and his tumor had given him such a jab of reverberating pain in the neck and head that he was no longer concerned with enlightening these boobies and exploding their nonsense. After all, it was only by chance he had landed in this clinic. He shouldn’t have had to live through such a crucial period of his illness in the company of people like this. But the main, the most terrible thing was that the tumor had not subsided or softened in the least after his injection the day before. The very thought gave him a cold feeling in the belly. It was all very well for Bone-chewer to talk about death. He was getting better.

Dyomka’s guest, the portly man without a voice, sat there holding his larynx to ease the pain. Several times he tried to intervene with something of his own or to interrupt the unpleasant argument, but nobody could hear his whisper and he was unable to talk any louder. All he could do was lay two fingers on his larynx to lessen the pain and help the sound. Diseases of the tongue and throat, which made it impossible to talk, are somehow particularly oppressive. A man’s whole face becomes no more than an imprint of this oppression. Dyomka’s guest now tried to stop the argument, making wide sweeps of his arms. Even his tiny voice was now more easily heard. He moved forward along the passageway between the beds.

“Comrades! Comrades!” he wheezed huskily. Even though the pain in his throat was not your own, you could still feel it. “Don’t let’s be gloomy! We’re depressed enough by our illnesses as it is. Now you, comrade”—he walked between the beds and almost beseechingly stretched out one hand as if to a deity (the other was still at his throat) toward the disheveled Kostoglotov sitting on high—“you were telling us such interesting things about birch fungus. Please go on!”

“Come on, Oleg, tell us about the birch fungus. What was it you said?” Sibgatov was asking.

The bronze-skinned Ni could only move his tongue with difficulty because part of it had dropped off during his previous course of treatment and the rest had now swollen, but indistinctly he too was asking Kostoglotov to continue.

The others were asking him to as well.

A disturbing feeling of lightness ran through Kostoglotov’s body. For years he had been used to keeping his mouth shut, his head bowed and his hands behind his back in front of men who were free. It had become almost a part of his nature, like a stoop you are born with. He hadn’t rid himself of it even after a year in exile. Even now it seemed the natural, simple thing to clasp his hands behind his back when he walked along the paths of the hospital grounds. But now these free men, who for so many years had been forbidden to talk to him as an equal, to discuss anything serious with him as one man to another or—even more bitter—to shake hands with him or take a letter from him—these free men were sitting in front of him, suspecting nothing, while he lounged casually on a window sill playing the schoolmaster. They were waiting for him to bolster up their hopes. He also realized that he no longer set himself apart from free men, as he used to, but was joining them in the common misfortune.

In particular he had grown out of the habit of speaking to a lot of people, of addressing any kind of conference, session or meeting. And yet here he was, becoming an orator. It all seemed wildly improbable to Kostoglotov, like an amusing dream. He was like a man charging full-tilt across ice, who has to rush forward, come what may. And so carried by the cheerful momentum of his recovery, unexpected but, it seemed, real, he went on and on.

“Friends!” he said, with uncharacteristic volubility. “This is an amazing tale. I heard it from a patient who came in for a checkup while I was still waiting to be admitted. I had nothing to lose, so straightaway I sent off a postcard with this hospital’s address on it for the reply. And an answer has come today, already! Only twelve days, and an answer! Dr. Maslennikov even apologizes for the delay because, it seems, he has to answer on an average ten letters a day. And you can’t write a reasonable letter in less than half an hour, can you? So he spends five hours a day just writing letters—and he doesn’t get a thing for it!”

“No, and what’s more, he has to spend four roubles a day on stamps,” Dyomka interjected.

“That’s right, four roubles a day. Which means a hundred and twenty a month. And he doesn’t have to do it, it’s not his job, he just does it as a good deed. Or how should I put it?” Kostoglotov turned maliciously toward Rusanov. “A humane act, is that right?”

But Pavel Nikolayevich was finishing reading a newspaper report of the budget, He pretended not to hear.

“And he has no staff, no assistants or secretaries. He does it all on his own time. And he doesn’t get any honor and glory either! You see, when we’re ill a doctor is like a ferryman: we need him for an hour and after that we forget he exists. As soon as he cures you, you throw his letters away. At the end of his letter he complains that his patients, especially the ones he’s helped, stop writing to him. They don’t tell him about the doses they take or the results. And then he goes on to ask me to write to him regularly—he’s the one who asks me, when we should be bowing down before him.”

In his heart Kostoglotov was convincing himself that he had been warmly touched by Maslennikov’s selfless industry, that he wanted to talk about him and praise him, because it would mean he wasn’t entirely spoiled himself. But he was already spoiled to the extent that he would not have been able to put himself out like Maslennikov day after day for other people.

“Tell us everything in the proper order, Oleg!” said Sibgatov, with a faint smile of hope.

How he wanted to be cured! In spite of the numbing, obviously hopeless treatment, month after month and year after year—suddenly and finally to be cured! To have his back healed again, to straighten himself up, walk with a firm tread, be a fine figure of a man! “Hello, Ludmila Afanasyevna! I’m all right now!”

They all longed to find some miracle doctor, or some medicine the doctors here didn’t know about. Whether they admitted as much or denied it, they all without exception in the depths of their hearts believed there was a doctor, or a herbalist, or some old witch of a woman somewhere, whom you only had to find and get that medicine from to be saved.

No, it wasn’t possible, it just wasn’t possible that their lives were already doomed.

However much we laugh at miracles when we are strong, healthy and prosperous, if life becomes so hedged and cramped that only a miracle can save us, then we clutch at this unique, exceptional miracle and believe in it!

And so Kostoglotov identified himself with the eagerness with which his friends were hanging on his lips and began to talk fervently, believing his own words even more than he’d believed the letter when he’d first read it to himself.

“Well, to start from the beginning, Sharaf, here it is. One of our old patients told me about Dr. Maslennikov. He said that he was an old pre-Revolutionary country doctor from the Alexandrov district near Moscow. He’d worked dozens of years in the same hospital, just like they used to do in those days, and he noticed that, although more and more was being written about cancer in medical literature, there was no cancer among the peasants who came to him. Now why was that?”

(Yes, why was that? Which of us from childhood has not shuddered at the mysterious? At contact with that impenetrable yet yielding wall behind which there seems to be nothing, yet from time to time we catch a glimpse of something which might be someone’s shoulder, or else someone’s hip? In our everyday, open, reasonable life, where there is no place for mystery, it suddenly flashes at us, “Don’t forget me! I’m here!”)

“So he began to investigate, he began to investigate,” repeated Kostoglotov. He never repeated anything, but now found pleasure in doing so. “And he discovered a strange thing; that the peasants in his district saved money on their tea, and instead of tea brewed up a thing called chaga, or, in other words, birch fungus…”

“You mean brown cap?” Podduyev interrupted him. In spite of the despair he’d resigned himself to and shut himself up in for the last few days, the idea of such a simple, easily accessible remedy burst upon him like a ray of light.

The people around him were all southerners, and had never in their lives seen a birch tree, let alone the brown-cap mushroom that grows under it, so they couldn’t possibly know what Kostoglotov was talking about.

“No, Yefrem, not a brown cap. Anyway, it’s not really a birch fungus, it’s a birch cancer. You remember, on old birch trees there are these … peculiar growths, like spines, black on top and dark brown inside.”

“Tree fungus, then?” Yefrem persisted. “They used to use it for kindling fires.”

“Well, perhaps. Anyway, Sergei Nikitich Maslennikov had an idea. Mightn’t it be that same chaga that had cured the Russian peasants of cancer for centuries without their even knowing it?”

“You mean they used it as a prophylactic?” The young geologist nodded his head. He hadn’t been able to read a line all evening, but the conversation had been worth it.

“But it wasn’t enough just to make a guess, you see? Everything had to be checked. He had to spend many, many years watching the people who were drinking the homemade tea and the ones who weren’t. Then he had to give it to people who developed tumors and take the responsibility for not treating them with other medicines. And he had to guess what temperature the tea ought to be at, and what sort of dose, and whether it should be boiled or not, how many glasses they ought to drink, whether there’d be any harmful aftereffects, and which tumors it helped most and which least. And all this took…”

“Yes, but what about now? What happens now?” said Sibgatov excitedly.

And Dyomka thought, could it really help his leg? Could it possibly save it?

“What happens now? Well, here’s his answer to my letter. He tells me how to treat myself.”

“Have you got his address?” asked the voiceless man eagerly, keeping one hand over his wheezing throat. He was already taking a notebook and a fountain pen from his jacket pocket. “Does he say how to take it? Does he say it’s any good for throat tumors?”

Pavel Nikolayevich would have liked to maintain his strength of will and punish his neighbor by a show of utter contempt, but he found he couldn’t let such a story and such an opportunity slip. He could no longer go on working out the meaning of the figures of the 1955 draft state budget which had been presented to a session of the Supreme Soviet. By now he had frankly lowered his newspaper and was slowly turning his face toward Bone-chewer, making no attempt to conceal his hope that he, a son of the Russian people, might also be cured by this simple Russian folk remedy. He spoke with no trace of hostility—he didn’t want to irritate Bone-chewer—yet there was a reminder in his voice. “But is this method officially recognized?” he asked. “Has it been approved by a government department?”

High up on his window sill, Kostoglotov grinned. “I don’t know about government departments. This letter”—he waved in the air a small, yellowish piece of paper with green-ink writing on it—“is a business letter: how to make the powder, how to dissolve it. But I suppose if it had been passed by the government, the nurses would already be bringing it to us to drink. There’d be a barrel of the stuff on the landing. And we wouldn’t have to write to Alexandrov.”

“Alexandrov.” The voiceless man had already written it down. “What postal district? What street?” He was quick to catch on.

Ahmadjan was also listening with interest and managing to translate the most important bits quietly to Mursalimov and Egenberdiev. Ahmadjan did not need the birch fungus himself because he was getting better, but there was one thing he didn’t understand.

“If the mushroom’s that good, why don’t the doctors indent for it? Why don’t they put it in their standing orders?”

“It’s a long business, Ahmadjan. Some people don’t believe in it, some don’t like learning new things and so are obstructive, some try to stop it to promote their own remedies, but we don’t have any choice.”

Kostoglotov answered Rusanov and answered Ahmadjan, but he didn’t answer the voiceless man or give him the address. So that no one would notice this, he pretended he hadn’t quite heard him or didn’t have time to answer, but in fact he didn’t want to give him the address. He didn’t want to because there was something insinuating about the voiceless man’s attitude, respectable though he looked. He had the figure and face of a bank manager, or even of the premier of a small South American country. Oleg felt sorry for honest old Maslennikov, who was ready to give up his sleep to write to people he didn’t know. The voiceless man would shower him with questions. On the other hand, it was impossible not to feel sorry for this wheezing throat which had lost the ring of a human voice, unvalued when we have it. But there again, Kostoglotov had learned how to be ill, he was a specialist in being ill, he was devoted to his illness. He had already read bits of Pathological Anatomy and managed to get explanations out of Gangart and Dontsova, and he’d got an answer from Maslennikov. Why should he, the one who for years had been deprived of all rights, be expected to teach these free men how to wriggle out from underneath the boulder that was crushing them? His character had been formed in a place where the law dictated: “Found it? Keep your trap shut. Grabbed it? Keep it under the mattress,” If everyone started writing to Maslennikov, Kostoglotov would never get another reply to his own letters.

It was not a deeply thought-out decision. It was all done through a movement of his scarred chin from Rusanov to Ahmadjan, past the man without a voice.

“But does he say how to use it?” asked the geologist. He had pencil and paper in front of him. He always had when he was reading a book.

“How to use it? All right, get your pencils and I’ll dictate,” said Kostoglotov.

Everyone rushed about asking each other for pencil and paper. Pavel Nikolayevich didn’t have anything (he’d left his fountain pen at home, the one with the enclosed nib, the new kind). Dyomka gave him a pencil. Sibgatov, Federau, Yefrem and Ni all wanted to write. When they were ready Kostoglotov began to dictate slowly from the letter, explaining how chaga should be dried, but not dried out, how to grate it, what sort of water to boil it in, how to steep it, strain it, and what quantity to drink.

Some of them wrote quickly, some clumsily. They asked him to repeat it, and warmth and friendliness spread through the ward. Sometimes they used to answer each other with such antipathy—but what did they have to quarrel over? They all had the same enemy, death. What can divide human beings on earth once they are all faced with death?

Dyomka finished writing. In his usual rough, slow voice, older than his years, he said, “Yes, but where can we get birch from? There isn’t any.”

They sighed. All of them, those who had left Central Russia long ago, some even voluntarily, as well as the ones who had never even been there, all now had a vision of that country, unassuming, temperate, unscorched by the sun, seen through a haze of thin sunlit rain, or in the spring floods with the muddy fields and forest roads, a quiet land where the simple forest tree is so useful and necessary to man. The people who live in those parts do not always appreciate their home; they yearn for bright blue seas and banana groves. But no, this is what man really needs: the hideous black growth on the bright birch tree, its sickness, its tumor.

Only Mursalimov and Egenberdiev thought to themselves that here too, in the plains and on the hills, there was bound to be just what they needed; because man is provided with all he needs in every corner of the earth, he only has to know where to look.

“We’ll have to ask someone to collect it and send it,” the geologist said to Dyomka. He seemed attracted by the idea of the chaga.

Kostoglotov himself, the discoverer and expounder of it all, had no one in Russia he could ask to look for the fungus. The people he knew were either already dead or scattered about the country, or he’d have felt awkward about approaching them, others were complete cityites who’d never be able to find the right birch tree, let alone the chaga on it. He could not imagine any greater joy than to go away into the woods for months on end, to break off this chaga, crumble it, boil it up on a campfire, drink it and get well like an animal. To walk through the forest for months, to know no other care than to get better! Just as a dog goes to search for some mysterious grass that will save him.

But the way to Russia was forbidden to him.

The other people there, to whom it was open, had not learned the wisdom of making sacrifices, the skill of shaking off inessentials. They saw obstacles where there were none. How could they get sick leave or a holiday, to go off on a search? How could they suddenly disrupt their lives and leave their families? Where were they to get the money from? What clothes should they wear for such a journey, and what should they take with them? What station should they get off at, and where should they go then to find out more about it?

Kostoglotov tapped his letter and went on, “He says here there are people who call themselves suppliers, ordinary enterprising people who gather the chaga, dry it and send it to you cash on delivery. But they charge a lot, fifteen roubles a kilogram, and you need six kilograms a month.”

“What right do they have to do that?” said Pavel Nikolayevich indignantly. His face became sternly authoritative, enough to scare any “supplier” who came before him or even make him mess his pants. “What sort of a conscience do they have, fleecing people for something that nature provides free?”

“Don’t shouth!” Yefrem hissed at him. (His way of distorting words was particularly unpleasant. It was impossible to tell whether he did it on purpose or because his tongue could not cope with them.) “D’you think you can just go into the woods and get it? You have to walk about in the forest with a sack and an ax. And in the winter you need skis.”

“But not fifteen roubles a kilogram, black marketeers, damn them!” Rusanov simply could not compromise on such a matter. Again the red patches began to appear on his face.

It was wholly a question of principle. Over the years Rusanov had become more and more unshakably convinced that all our mistakes, shortcomings, imperfections and inadequacies were the result of speculation. Scallions, radishes and flowers were sold on the street by dubious types, milk and eggs were sold by peasant women in the market, and yoghurt, woolen socks, even fried fish at the railway stations. There was large-scale speculation too. Trucks were being driven off “on the side” from state warehouses. If these two kinds of speculation could be torn up by the roots, everything in our country could be put right quickly and our successes would be even more striking. There was nothing wrong in a man strengthening his material position with the help of a good salary from the state and a good pension (Pavel Nikolayevich’s dream was to be awarded a special, personal pension). Such a man had earned his car, his cottage in the country, and a small house in town to himself. But a car of the same make from the same factory, or a country cottage of the same standard type, acquired a completely different, criminal character if they had been bought through speculation. Pavel Nikolayevich dreamed, literally dreamed, of introducing public executions for speculators. Public executions would speedily bring complete health to our society.

“All right, then.” Yefrem was angry too. “Stop shouthing and go and organize the supply yourself. A state supply if you like. Or through a coop. If fifteen roubles is too much for you, don’t buy it.”

Rusanov realized this was his weak spot. He hated speculators, but his tumor would not wait for the new medicine to be approved by the Academy of Medical Science or for the Central Russian cooperatives to organize a constant supply of it.

The voiceless newcomer, who with his notebook looked like a reporter from an influential newspaper, almost climbed onto Kostoglotov’s bed. He spoke insistently and hoarsely, “The address of the suppliers? Is the address of the suppliers in the letter?”

Pavel Nikolayevich too got ready to write down the address.

But for some reason Kostoglotov didn’t reply. Whether there was an address in the letter or not, he just didn’t answer. Instead he got down from the window sill and began to rummage under the bed for his boots. In defiance of all hospital rules he kept them hidden there for taking walks.

Dyomka hid the prescription in his bedside table. Without trying to learn more, he began to lay his leg very carefully on the bed. He didn’t and couldn’t have that sort of money.

Yes, the birch tree helped, but it didn’t help everyone.

Rusanov was really quite embarrassed. He had just had a skirmish with Bone-chewer, not for the first time in the three days, either, and was now patently interested in his story and dependent on him for the address. Thinking he ought to butter Bone-chewer up a bit, he started, unintentionally and involuntarily, as it were, on something that united them, and said with a good deal of sincerity, “Yes, what on earth can one imagine worse than this…” (this cancer? He hadn’t got cancer!) “… than this … oncological … in fact, cancer?”

But Kostoglotov wasn’t in the least touched by this mark of trust coming from someone so much older, senior in rank and more experienced than he was. Wrapping round his leg a rust-colored puttee that he’d just been drying, and pulling on a disgusting, dilapidated rubber-cloth kneeboot with coarse patches on the creases, he barked, “What’s worse than cancer? Leprosy.”

The loud, heavy, threatening word resounded through the room like a salvo.

Pavel Nikolayevich grimaced, peaceably enough. “Well, it depends. Is it really worse? Leprosy is a much slower process.”

Kostoglotov stared with a dark and unfriendly expression into Pavel Nikolayevich’s bright glasses and the bright eyes beyond them.

“It’s worse because they banish you from the world while you are still alive. They tear you from your family and put you behind barbed wire. You think that’s any easier to take than a tumor?”

Pavel Nikolayevich felt quite uneasy: the dark, burning glance of this rough, indecent man was so close to him, and he was quite defenseless.

“Well, what I mean is, all these damn diseases…”

Any educated man would have seen at this point that it was time to make a conciliatory gesture, but Bone-chewer couldn’t understand this. He couldn’t appreciate Pavel Nikolayevich’s tact. He rose to his full, lanky height and put on a roomy, dirty gray fustian woman’s dressing gown that reached down almost to his boots (it served him as an overcoat when he went for walks). Then he announced in his self-satisfied way, thinking how learned he sounded, “A certain philosopher once said, if a man never became ill he would never get to know his own limitations.”

Taking a rolled-up army belt, four fingers wide with a five-pointed star on the buckle, from the pocket of the woman’s dressing gown he’d wrapped himself in, he put it round himself, only taking care not to tie it too tight in the place where his tumor was. Chewing a wretched, cheap little cigarette end, the sort that goes out before it’s all smoked, he walked to the door.

The interviewer with the wheezing throat retreated before Kostoglotov along the passageway between the beds. Still looking like some sort of banker or minister, he nevertheless kept begging Kostoglotov to answer him, deferring to him as if he were some bright star of oncological science who was about to leave the building forever. “Tell me, roughly, in what percentage of cases does a tumor of the throat turn out to be cancer?”

It is disgraceful to make fun of illness or grief, but even illness and grief must be borne without lapsing into the ridiculous. Kostoglotov looked at the lost, terrified face of the man who had been flitting round the ward so absurdly. He had probably been rather domineering before he got his tumor. Even the understandable habit of holding the throat with the fingers while speaking seemed somehow funny when he did it.

“Thirty-four,” said Kostoglotov. He smiled at him and stood aside.

Hadn’t he done too much cackling himself today? Hadn’t he perhaps said too much, said something he shouldn’t have?

But the restless interviewer would not leave him. He hurried down the stairs after him, bending his portly frame forward, still talking and wheezing over Kostoglotov’s shoulder: “What do you think, comrade? If any tumor doesn’t hurt, is it a good or a bad sign? What does it show?”

Tiresome, defenseless people.

“What do you do?” Kostoglotov stopped and asked him.

“I’m a lecturer.” A big-eared man with gray, sleek hair, he looked at Kostoglotov hopefully, as at a doctor.

“Lecturer in what? What subject?”

“Philosophy,” replied the bank manager, remembering his former self and regaining some of his bearing. Although he had shown a wry face all day, he had forgiven Kostoglotov his misplaced and clumsy quotations from the philosophers of the past. He wouldn’t reproach him, he needed the suppliers’ addresses.

“A lecturer, and it’s your throat!” Kostoglotov shook his head from side to side. He had no regrets about not giving the suppliers’ addresses out loud in the ward. By the standards of the community that for seven years had dragged him along like a slab of metal through a wire-drawing machine, only a stupid sucker would do a thing like that. Everyone would rush off and write to these suppliers, the prices would be inflated, and he wouldn’t get his chaga. It was his duty, though, to tell a few decent people one by one. He’d already made up his mind to tell the geologist, even though they’d exchanged no more than ten words, because he liked the look of him and the way he’d spoken up in defense of cemeteries. And he’d tell Dyomka, except that Dyomka didn’t have any money. (In fact Oleg didn’t have any either, there was nothing for him to buy the chaga with.) And he would give it to Federau, Ni, Sibgatov, his friends in distress.[4] They would all have to ask him one by one, though, and anyone who didn’t ask would be left out. But this philosophy lecturer struck Oleg as a foolish fellow. What did he churn out in his lectures anyway? Perhaps he was just clouding people’s brains? And what was the point of all his philosophy if he was so completely helpless in the face of his illness?… But what a coincidence—in the throat, of all places!

“Write down the suppliers’ addresses,” Kostoglotov commanded. “But it’s only for you!” The philosopher, in grateful haste, bent down to write.

After he had dictated it, Oleg managed to tear himself away. He hurried to fit in his walk before they locked the outer door.

There was no one outside on the porch.

Oleg breathed in the cold, damp, still air happily, then, before it had time to cleanse him, he lit up a cigarette. Whatever happened, his happiness could never be complete without a cigarette (though Dontsova was not the only one now to have warned him to stop smoking; Maslennikov too had found room to mention it in his letter).

There was no wind or frost. Reflected in a windowpane he could see a nearby puddle. There was no ice on its black water. It was only the fifth of February and already it was spring. He wasn’t used to it. The fog wasn’t fog: more a light prickly mist that hung in the air, so light that it did not cloud but merely softened and blurred the distant lights of street lamps and windows.

On Oleg’s left, four pyramidal poplars towered high above the roof like four brothers. On the other side a poplar stood on its own, but bushy and the same height as the other four. Behind it there was a thick group of trees in a wedge of parkland.

From the unfenced stone porch of Wing 13 a few steps led down to a sloping asphalt pathway lined on both sides by an impenetrable hedge. It was leafless for the moment, but its thickness announced that it was alive.

Oleg had come out for a stroll along the pathways in the park, his leg, with each step and stretch, rejoicing at being able to walk firmly, at being the living leg of a man who had not died. But the view from the porch held him back, and he finished his cigarette there.

There was a soft light from the occasional lamps and windows of the wings opposite. By now there was hardly anyone walking along the paths. And when there was no rumble from the railway close by at the back, you could just hear the faint, even sound of the river, a fast-foaming mountain stream which rushed down behind the nearby wings, under the side of the hill.

Further on, beyond the hill and across the river, there was another park, the municipal one, and perhaps it was from there (except that it was cold) or from the open windows of a club that he could hear dance music being played by a brass band. It was Saturday and there they were dancing. Couples were dancing together …

Oleg was excited by all his talking and the way they’d listened to him. He was seized and enveloped by a feeling that life had suddenly returned, the life with which just two weeks ago he had closed all accounts. Though this life promised him nothing that the people of this great town called good and struggled to acquire: neither apartment, property, social success nor money, there were other joys, sufficient in themselves, which he had not forgotten how to value: the right to move about without waiting for an order; the right to be alone; the right to gaze at stars that were not blinded by prison-camp searchlights; the right to put the light out at night and sleep in the dark; the right to put letters in a letterbox; the right to rest on Sunday; the right to bathe in the river. Yes, there were many, many more rights like these.

And among them was the right to talk to women.

His recovery was giving him back all these countless, wonderful rights.

The music from the park just reached him. Oleg heard it—not the actual tune they were playing, but as if it were Tchaikovsky’s Fourth Symphony, its restless strained beginning ringing inside him, one incomparable melody. It was the melody (Oleg interpreted it in his own way, although perhaps it ought to be understood differently) in which the hero is returned to life or perhaps regaining his vision after being blind. He gropes with his fingers, as it were, slides his hand over things or over a face that is dear to him, touching them, still afraid to believe his good fortune: that these things really exist, that his eyes are beginning to see.

... ====================================== ===== ...

Pavel Nikolaevich was encouraged that his wife would come. Of course, she couldn’t help him with anything real, but how much it meant to pour out to her: how bad he felt; how the injection didn’t help at all; what nasty people in the ward. It’s easier to sympathize. And ask her to bring some book - cheerful, modern. And a fountain pen - in order not to end up as funny as yesterday, the guy borrowed a pencil to write down the recipe. Yes, and the main thing is to punish about the mushroom, about the birch mushroom.

In the end, all is not lost: medications will not help - there are different remedies. The most important thing is to be optimistic.

... ====================================== ===== ...

The time was approaching for her to leave anyway, and she began to take it out of her shopping bag and show her husband what she had brought him to eat. The sleeves of her fur coat were so wide with silver fox cuffs that they barely fit into the gaping mouth of the bag.

And then, seeing food (of which he still had plenty left in his nightstand), Pavel Nikolaevich remembered something else that was more important to him than any food and drink, and where he had to start today - he remembered chaga, birch mushroom ! And, perking up, he began to tell his wife about this miracle, about this letter, about this doctor (maybe a charlatan) and about what they need to figure out now, who to write to, who will pick up this mushroom for them in Russia.

— After all, there, around K*, we have as many birch trees as we like. What does it cost for Minai to organize this for me?! Write to Minay now! And for someone else, there are old friends, let them take care! Let everyone know what situation I'm in!

... ====================================== ===== ...

Angelina turned around, wondering why else Kostoglotov was here, but Lev Leonidovich also looked higher than her head - a little with humor. There was something unnameable in his face, which is why Kostoglotov decided to continue:

- And also, Lev Leonidovich, I wanted to ask you: have you heard about the birch mushroom, about chaga?

“Yes,” he confirmed quite willingly.

— How do you feel about him?

—It's hard to say. I admit that some specific types of tumors are sensitive to it. Stomach, for example. People in Moscow are going crazy with him now. They say that within a radius of two hundred kilometers they have picked out all the mushrooms; you won’t find them in the forest.

... ... ...

Notes

[1] ↑ Zvezda (Star) is a well-known literary monthly which attracted official criticism after the war because of its “liberalism.”

[2] ↑ Tolstoy was excommunicated by the Holy Synod, the ruling body of the Russian Orthodox Church under the Tsars.

[3] ↑ Nikolai Ostrovsky, a Soviet writer whose most important character attempted to be of use to the Party even from his deathbed.

[4] ↑ They all belonged to deported nationalities and were exiles like Kostoglotov.